Mastering Baking: Your Essential Guide to Understanding Different Types of Flour

Have you ever wondered why some breads are wonderfully chewy, while cakes are incredibly light and tender? The secret often lies in one fundamental ingredient: flour. This comprehensive guide delves into the fascinating world of baking flours, exploring their unique characteristics and how they impact your baked goods. Prepare to unlock the science behind your favorite recipes and elevate your baking game!

Today, we’re diving deep into the world of flour – exploring all the different varieties, understanding their unique properties, and discovering when and why to use them for various baking applications. Whether you’re a seasoned baker or just starting your culinary journey, this guide will demystify one of the most essential ingredients in your pantry.

This article will get a bit “nerdy” and technical, but in the best way possible! Much like understanding the nuances of different cooking salts, comprehending flour can profoundly transform your baking results. To keep things focused and highly practical, we’ll concentrate on baking flour varieties primarily produced from various strains of wheat. All the flours discussed here are standard types readily available in most grocery stores.

If you’re someone who thrives on understanding the whys and hows of baking, you’re going to love this post. Have you ever pondered the key differences between bread flour and all-purpose flour? Or perhaps questioned what pastry flour is used for and why it’s critical for certain recipes? And what makes cake flour so magical for producing those famously light-as-air sponge cakes? This guide will break down every essential detail. It’s packed with information designed to turn you into a more informed and confident baker.

Let’s get started on our flour journey!

Wheat: The Foundation of Flour

All wheat flours originate from the milling of wheat kernels, also widely known as wheat berries – the very same whole grains you might spot in the bulk bins of your local grocery store. In my own kitchen, I consistently rely on Bob’s Red Mill flours, a brand I trust for its quality and consistency (you can read more about my reasons here). The gluten percentages referenced throughout this post are specific to their milling specifications and product lines, but they generally provide a reliable benchmark consistent with other reputable flour brands. It’s worth noting that as flours naturally age, their gluten and protein content can subtly increase, qualities that are often desirable but develop over time.

Understanding the Wheat Kernel

Each wheat kernel is a marvel of nature, ingeniously comprised of three distinct parts:

- Germ: This is the embryo of the wheat kernel, rich in natural oils, essential nutrients, vitamins, and healthy fats. It’s the part that would sprout into a new plant if given the chance.

- Bran: The protective outer shell of the kernel. Bran is an excellent source of dietary fiber, minerals, and various antioxidants. It gives whole wheat products their distinct color and texture.

- Endosperm: This constitutes the largest part of the kernel, serving as the primary food supply for the germ. It consists predominantly of protein and starch molecules, which are crucial for the structure and texture of baked goods.

When producing all-purpose or most refined flours, the germ and bran are meticulously removed during the milling process. This leaves only the endosperm, which is then ground into very fine particles, often referred to as streams. These streams are carefully analyzed for their protein and starch content, allowing millers to precisely blend them into specific flour types with predetermined baking characteristics. Stone-ground flours stand as a notable exception, as their traditional milling process often allows for some presence of germ and bran in the final product, even when labeled as refined.

In contrast, whole wheat flours are produced by milling the entire wheat kernel – germ, bran, and endosperm – without any components removed. This comprehensive milling process results in whole wheat flours generally being higher in protein than their all-purpose counterparts, and significantly more nutrient-dense due to the inclusion of all three parts of the grain.

Unraveling the Mystery of Gluten

Gluten is a term that often sparks curiosity, and sometimes confusion, in the baking world. Simply put, gluten is a complex network of specific proteins – primarily glutenins and gliadins – found naturally in wheat and other grains like barley and rye. In its dry, dormant state, wheat flour’s proteins possess minimal discernible structure. However, the moment water is introduced, a remarkable transformation begins. These gluten proteins hydrate, change shape, and start to form bonds with one another, creating intricately coiled, yet remarkably elastic, structures. Imagine them as microscopic, highly stretchable spring-like networks, much like a slinky.

How Gluten Works in Baking

Just like a slinky, these protein structures possess an extraordinary ability to stretch and expand significantly. They can extend and enlarge, yet inherently provide a strong, flexible framework and shape. This unique characteristic of gluten is what empowers us to create a vast array of beloved baked goods: from the airy, chewy structure of artisanal breads with their delightful air pockets to the firm, al dente texture of pasta strands, and the delicate, long sheets required for puff pastry that won’t tear during rolling. Gluten acts as the architectural backbone, trapping gases (like carbon dioxide produced by yeast or baking powder) and allowing the dough or batter to rise and hold its shape.

A Very Important Note: While whole wheat flours are indeed rich in protein and gluten, the presence of the coarse bran and germ particles within the flour can actually interfere with the optimal development of strong gluten strands. These sharp particles can sever the delicate gluten network as it forms, leading to weaker, less elastic gluten. This fundamental difference is precisely why 100% whole wheat breads and pastries often exhibit a denser, heavier texture compared to those made with refined flours. Strong gluten is essential for the significant expansion and airy crumb that many bakers desire.

The development of gluten is also heavily influenced by hydration and manipulation. As you add more water to flour, you facilitate the formation of more extensive gluten networks. When this mixture is subsequently worked, stretched, or handled (think: the rhythmic motion of kneading dough), the proteins are continually stretched and aligned, becoming even more elastic and robust. Conversely, the less a mixture is worked, the less concentrated and developed the gluten will be. Understanding this principle is crucial, as some types of baking greatly benefit from significant gluten development (e.g., yeast breads, pizza doughs, pasta, puff pastry), while certain others require minimal gluten formation to achieve their desired tender texture (e.g., pancakes, quick breads leavened with baking powder/soda, pie dough, cakes).

Factors Affecting Gluten Strength

Beyond water and manipulation, other ingredients commonly used in baking can either strengthen or weaken the gluten network. Grasping these interactions is vital for mastering various baking techniques and for successful recipe development. For instance, the ions present in salt tend to tighten and increase gluten strength, contributing to a more resilient dough. Conversely, larger quantities of sugar and fat (as found in many sweet pastries and rich cakes) will decrease overall gluten strength, making the dough more tender and less elastic. Acidity can also have a weakening effect on gluten, which is why some pastry dough recipes might recommend adding a touch of vinegar or lemon juice to achieve a more tender, flaky result.

A Deep Dive into Different Baking Flours

The world of wheat flours is diverse, with various strains of wheat possessing inherently different protein contents. Hard red winter wheat, for example, typically yields higher protein (and thus more gluten) than soft white wheat. Millers strategically utilize these differences to create the distinct types of flours we use in our kitchens.

Below, I’ve outlined basic protein ranges for various flour types. It’s important to remember that these percentages can vary somewhat from brand to brand, but reputable millers like Bob’s Red Mill maintain strict protein thresholds to ensure consistency and reliability across their products – a critical factor for predictable baking results. While each wheat crop naturally varies, these specified protein ranges are used by Bob’s Red Mill to test every shipment of wheat they receive:

Unbleached All-Purpose Flour (12% – 13% Protein)

Considered the quintessential “workhorse” of all flour blends, unbleached all-purpose flour is my basic flour of choice for nearly every baking project. Unless a recipe explicitly specifies another flour type, it’s generally safe to assume that most baking recipes are formulated with all-purpose flour in mind. It’s crucial to note, however, that the definition and protein percentage of all-purpose flour in the United States can differ significantly from “plain flour” or “standard flour” in other countries, so always check local specifications if adapting international recipes.

All-purpose flour is typically milled from hard red winter wheat. As a refined flour, its bran and germ are removed during milling, resulting in a lighter-colored flour with a moderate protein content. This mid-level protein balance makes it incredibly versatile, capable of producing acceptable results across a wide spectrum of baking applications, from fluffy muffins to sturdy pie crusts and tender cookies.

Bleached vs. Unbleached All-Purpose Flour

The distinction between bleached and unbleached flour is significant. Bleached flours undergo chemical treatment with agents like benzoyl peroxide or chlorine dioxide, which whiten the flour and accelerate its aging process. Some bleached flours may also contain bromate, an ingredient often banned in other countries due to health concerns, which is added to improve rise and elasticity. Historically, bleaching was a rapid solution to produce vast quantities of flour for mass consumption.

As an unintended consequence of the bleaching process, bleached all-purpose flours generally have a slightly lower protein content than their unbleached counterparts. Some pastry chefs might recommend it for extremely delicate pastries for this reason. However, I personally rarely, if ever, use bleached flours due to the chemical processing. In contrast, high-quality unbleached flours, such as those from Bob’s Red Mill, contain no chemicals. They achieve enhanced rise and elasticity naturally by incorporating a small amount of malted barley flour into their blend, which acts as a natural enzyme to improve dough performance.

Bread Flour (12.5% – 15% Protein)

Bread flour is specifically milled from hard red spring wheat, a variety known for its inherently high protein content. Like all-purpose flour, bread flour is a refined product, meaning the bran and germ of the wheat kernel have been removed. The significantly higher protein level in bread flour is its defining characteristic, allowing for maximum gluten development when combined with water and kneaded. This robust gluten network is essential for creating doughs that can stretch, expand, and effectively trap large amounts of gas (produced by yeast, for example). The result? Loaves of artisanal bread boasting beautiful, airy crumb structures, excellent volume, and a satisfyingly chewy texture. This enhanced chewiness is also why very high-protein flours, like durum wheat, are primarily used to produce most store-bought pasta.

Therefore, higher protein bread flour is indispensable for doughs and baked goods that demand superior elasticity, strength, and structure. Think of recipes like yeast breads of all kinds, pizza doughs, and certain laminates or stretched pastry doughs such as puff pastry or strudel dough. Occasionally, some cookie recipes will incorporate a small amount of bread flour alongside all-purpose flour to achieve a chewier texture.

100% Whole Wheat Flour (13.5% Protein)

Unlike refined all-purpose flour, true whole wheat flours are produced by milling the entire wheat kernel – comprising the germ, bran, and endosperm – typically from hard red wheat varieties. This is why it’s also referred to as whole grain flour. The inclusion of the bran and germ imparts a slightly darker color, a more robust and nutty flavor profile, and significantly higher nutritional content compared to refined flours. This is particularly true for stone-ground whole wheat flours, which retain maximum integrity from the grain.

Since whole wheat flours contain all parts of the wheat kernel, they are generally higher in protein than all-purpose flours. However, and this is a critical point, despite its high protein content, the abrasive presence of the bran and germ particles makes it more challenging for whole wheat flour to develop a strong, elastic gluten network comparable to that of all-purpose or bread flour. These sharp particles can physically disrupt the delicate gluten strands as they form and stretch. This inherent structural limitation is the primary reason why 100% whole wheat breads and other baked goods often tend to be denser, heavier, and less airy in texture.

Flours with higher protein content, including whole wheat flour, also tend to absorb more liquid than lower protein flours. Therefore, when substituting whole wheat flour for all-purpose flour in most recipes, it’s often necessary to adjust the liquid amounts slightly to prevent the dough or batter from becoming too dry. To incorporate the nutritional benefits and enhanced flavor of whole wheat without significantly impacting the structure of your baked goods, a common strategy is to substitute a small portion (e.g., 25-50%) of all-purpose flour with an equal quantity of whole wheat flour. This often yields excellent results with minimal textural compromise.

Storage Tips for Whole Wheat Flour

Because whole wheat flours contain the natural oils present in the wheat germ, they are more susceptible to rancidity and thus have a shorter shelf life than refined all-purpose flours. To preserve its nutrients and prolong freshness, I highly recommend storing whole wheat flour in the refrigerator or, for longer-term storage, in the freezer, especially if you don’t plan to use an entire bag quickly. Ensure it’s in an airtight container to prevent moisture absorption and odor contamination.

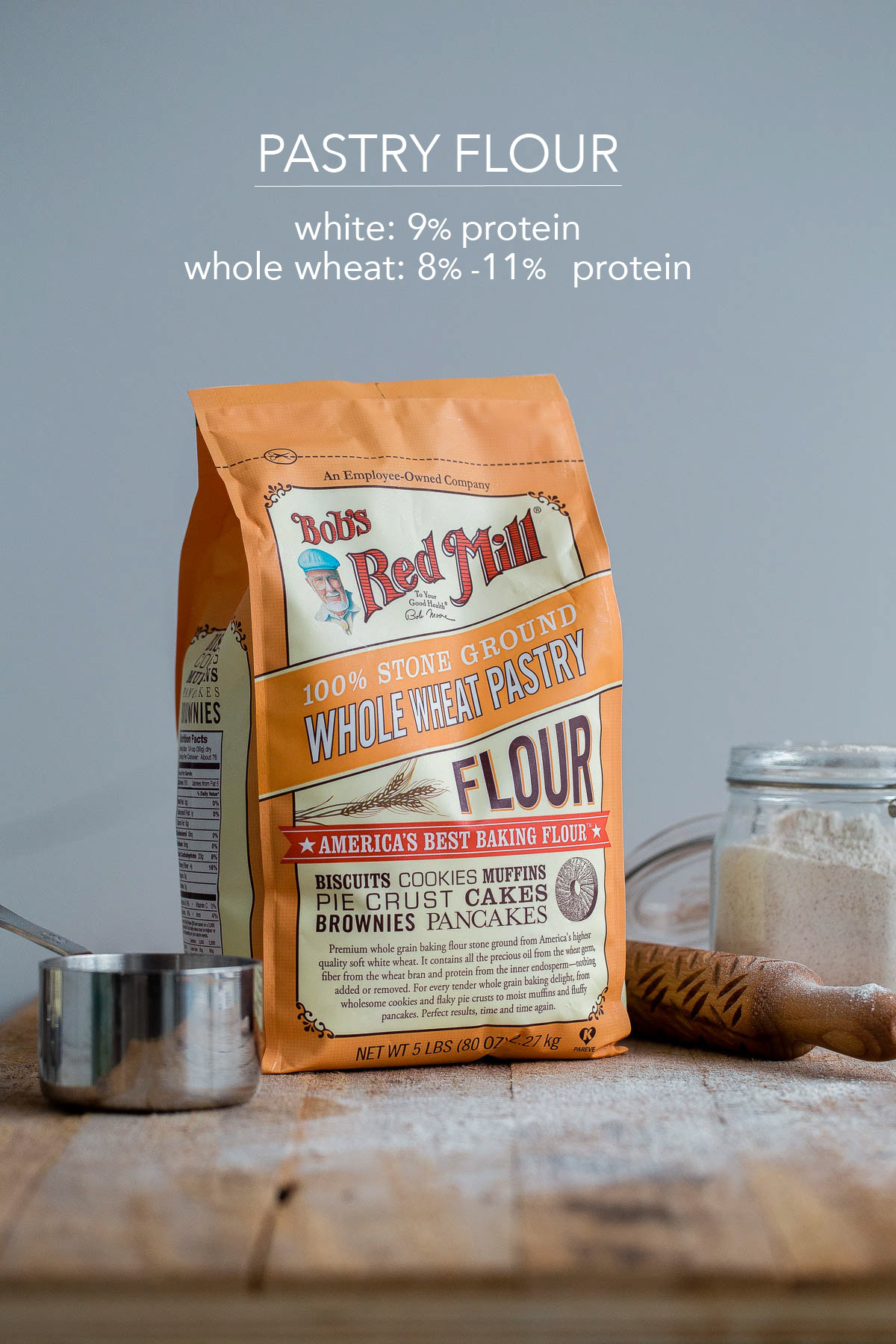

Pastry Flour (8% – 11% Protein)

In contrast to many other flours derived from hard red wheat, pastry flour is uniquely milled from a different strain: soft white wheat. This particular wheat variety contains significantly less protein than red wheat, which directly translates to flours that are lower in protein and, consequently, produce considerably less gluten development when hydrated. This minimal gluten formation is precisely why pastry flour is coveted by bakers.

Low gluten development is highly desirable for baked goods where a tender, crumbly, or flaky texture is paramount, rather than elasticity or chewiness. This includes items leavened by baking soda and baking powder (like quick breads, muffins, cakes, and pancakes), as well as delicate pie doughs and biscuits. The reduced gluten ensures a tender, melt-in-your-mouth quality that cannot be achieved with higher protein flours.

While unbleached refined pastry flour (from which the germ and bran have been removed, typically around 9% protein) is an excellent choice, I particularly favor whole wheat pastry flour (ranging from 8% to 11% protein) as my preferred whole grain flour for baking tender treats. It truly offers the best of both worlds: the full nutritional benefits of whole grains combined with the tenderizing properties of low-protein flour. I often substitute it 1:1 for all-purpose flour in many recipes, such as this poppy seed bread, with consistently great success. The difference in texture and flavor compared to all-purpose flour is often indiscernible.

Whole wheat pastry flour empowers you to produce deliciously tender, fluffy, and 100% whole grain baked goods – replete with all the added nutritional value – that would otherwise be difficult to achieve with standard whole wheat flour (which has a higher protein content of 13.5% and a greater tendency to produce dense results).

100% White/Ivory Whole Wheat Flour (13% – 16% protein)

White whole wheat flour is a relatively newer entrant to the market, offering an exciting alternative for whole grain baking. It is produced by milling the entire kernel of naturally white winter wheat varieties, which are inherently high in protein. Bob’s Red Mill’s excellent version is known as ivory whole wheat flour. Interestingly, and perhaps counter-intuitively for some, it actually possesses a protein content that is often higher than that of traditional hard red whole wheat flour.

Despite its “white” designation, white whole wheat flour is 100% whole grain, meaning it contains all the bran, germ, and endosperm. Its lighter color, however, comes from the fact that it’s milled from wheat kernels that are naturally pale, rather than the darker red wheat. This also contributes to its slightly sweeter and milder flavor profile compared to traditional whole wheat flour, while still offering identical nutritional benefits. Many bakers prefer it for its less assertive taste and more familiar appearance in baked goods.

Given its naturally high protein content, white/ivory whole wheat flour performs exceptionally well as a whole grain substitute for bread flour or in other baked goods that greatly benefit from increased elasticity and robust gluten development. This makes it ideal for recipes like yeast doughs, pizza, puff pastry, and strudel dough, where its strength can shine. However, because its primary characteristic is strength rather than tenderness, white/ivory whole wheat flour is less ideal for baked goods where tenderness is the goal. For this reason, I typically avoid using it in baking soda and baking powder leavened batters (such as quick breads, muffins, cakes, and pancakes) or in pie doughs, opting instead for whole wheat pastry flour for those applications.

Cake Flour (6.5% protein)

Last but certainly not least, cake flour stands at the opposite end of the protein spectrum from bread flour. It is meticulously milled from extremely low-protein wheat strains, sometimes referred to as club wheat. This selection results in a flour that yields minimal gluten development when combined with water – a characteristic that would be catastrophic for achieving a chewy bread, but is absolutely magical for crafting delicate baked goods. Think of angel food cakes, ethereal Genoise sponges, or truly light-as-air sponge cakes, feather-light biscuits, and wonderfully tender muffins.

Now that we’ve thoroughly explored the basics of gluten, it’s easy to grasp why employing a flour with a mere 6.5% protein content versus an all-purpose flour at 12% to 13% protein would lead to two entirely different outcomes in your baking. The minimal gluten in cake flour prevents the formation of a strong, chewy structure, allowing other ingredients to dominate and contribute to a tender crumb.

Beyond its low protein, cake flour is also distinguished by its incredibly fine texture, a result of extra milling and sifting. This ultra-fine grind allows it to absorb liquids very quickly and evenly. It’s worth noting that many generic cake flours on the market are bleached and often “cut” or blended with cornstarch (always check the ingredients label!). Adding cornstarch effectively dilutes the protein and gluten content of the flour even further, enhancing its tenderizing effect. This is also the scientific basis behind popular DIY cake flour recipes, which instruct you to combine all-purpose flour with a small amount of cornstarch.

In stark contrast, Bob’s Red Millcake flour is unbleached, contains no chemical additives, and includes zero cornstarch, relying purely on the inherent low protein of the wheat for its properties. I personally love this product! While I don’t reach for cake flour for every baking project, when a recipe calls for that ultimate delicate, lighter-than-air texture, it is truly indispensable.

Conclusion: Your Flour, Your Bake

As we’ve seen, the various types of wheat flour are far from interchangeable. Each possesses a distinct protein content, milling process, and resulting gluten potential, all of which profoundly impact the final texture, structure, and flavor of your baked goods. Once you develop a fundamental understanding of these basic properties, a whole new world of baking possibilities opens up. This knowledge empowers you to confidently experiment, create your own unique flour blends, and get truly creative in the kitchen. More importantly, it allows you to precisely tailor your baked goods to your own desired liking – whether you crave a supremely chewy bread, an impossibly tender cake, or a flaky, buttery pastry.

Embrace the science, understand your ingredients, and transform your baking from following instructions to truly mastering the craft!

Further Reading & Resources

If your curiosity for baking science has been piqued and you’re eager to learn even more, here are a handful of my favorite cooking resources and books ([affiliate links]):

- On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen by Harold McGee

- Cookwise: The Hows & Whys of Successful Cooking by Shirley O. Corriher

- The Pie and Pastry Bible by Rose Levy Beranbaum

- The Professional Pastry Chef: Fundamentals of Baking and Pastry by Bo Friberg

- Ratio: The Simple Does Behind the Craft of Everyday Baking by Michael Ruhlman

For more insights into essential kitchen tools and ingredients, find more kitchen essentials posts here.